Stop Sucking At Build Environments

It’s become painfully obvious to me recently that developers tend to be really, really bad at setting up a decent build environment. Xcode is shonky at the best of times, but it certainly doesn’t help if you let carelessness or ignorance lead to complexity creep. Eventually, you’ll end up with a project requiring 10 different build scripts, all with their own sets of assumptions and dependencies (such as ruby, brew, pod, perl versions).

Jenkins

Jenkins is shit. No really, it’s actually really rather terrible. When you think about it, it’s basically just a pretty (well ok, it’s not pretty by anyone’s definition) interface over cron. For the purposes of continuous integration, there’s pretty much nothing Jenkins gives you that you couldn’t achieve with a cron job, a decent build script in your repository and a disciplined filing system.

Maybe that’s a bit harsh, but from my personal experiences from it, most of the things it’s good at is solving problems that it’s responsible for creating in the first place. Your net gain from using Jenkins is damn-near close to zero, but you inherit a massive amount of maintainence burden.

It’s a prime example of what I was talking about a couple of days ago:

If your software isn’t at least as nice to use as the proprietary stuff, why do you even bother? You shouldn’t just settle for mediocrity and hope that because you’re open source you’ll get a decent userbase of digital hipsters.

I stand by that statement, especially in the face of the horror that is Jenkins. Rather than focus on building something delightful that’s really useful to a whole bunch of people, they’ve instead focused on building a “one size fits all” solution to build servers that actually serves no unique practical purpose whatsoever. It’s like they focused on being Enterprise FizzBuzz compliant at the expense of actually doing anything useful.

The situation with building for Xcode using Jenkins is pretty miserable. There is an Xcode plugin for Jenkins but they’re very clearly not up to the task of keeping it up to date with the constantly evolving Xcode. This is not something you use if you want reliability, no sir, you use build scripts!

Build scripts in Jenkins are a pretty fragile thing. The gist of it is, you’ll

be invoking xcodebuild at some stage, but before and after that there’ll be

a heap of codesigning hell. To top it all off, even if you manage to get the

thing to produce the correct IPA, Jenkins provides no functionality to host the

IPA for iOS clients to download.

After many days of research, and a hell of a lot of trial-and-error, eventually we managed to MacGuyver a solution where all the moving parts worked together – only to have everything fall apart when we had to revoke our distribution certificate.

So, since our build server was fucked anyway, why not try something new and shiny?

Xcode Server

First off, Xcode Server is horribly buggy. The amount of outstanding bugs in this thing is absolutely horrifying. Even some of the most basic things are completely broken:

- Don’t trust the Xcode Server to generate SSH keys. The keys it generates

are a damn lie and will never actually be used when authenticating with

your server. If you need to authenticate with the repo server using SSH

keys, generate them manually in the terminal using

ssh-keygenand copy them manually into the Xcode Server. Yes, one-by-one. Yes, recursively for each submodule. Isn’t programming a neat gig? - If you need to properly sign your archive – you know, so people can use

the builds – you’ll need to manually put the provisioning profile into

/Library/Server/Xcode/ProvisioningProfilesyourself. There are ways to completely automate this using schemes. Ask me nicely and I might show you one day. - If your build system modifies the

.xcodeproj– CocoaPods users pay attention – then it will immediately fail in weird and wonderful ways. - Recurring builds based on time (i.e Daily builds, Hourly builds) may or may not work. This might be related to whether your server has power management settings that puts it to sleep on a schedule, which we do to be green; sleep the servers in the evening when everyone’s at home. One server we set up has this stuff working reliably, whereas the other never works.

- Builds based on polling the repo for commits may or may not work. Both our servers have been doing this reliably for the last couple of days but there are plenty of reports that this isn’t working for some, so YMMV.

- If your repository has submodules, prepare for a world of hurt. It’s

possible to get it working, but keep in mind the following caveats:

- Submodules must not be in a detached HEAD state when you create the bot. Doing so will cause Xcode Server to think that the branch the submodules are on is literally the literal string “(detached head abcdef)”, which will obviously cause big problems when it tries to checkout the correct commit in each submodule.

- Because of the above, you must create your bot from within Xcode. The web interface for creating bots doesn’t support submodules at all.

- You MUST change the branch your submodules are in using Xcode, not the

gitcommand line or any other git tool. Xcode isn’t smart enough to realise the branch has changed if you don’t change it in Xcode, so it’ll continue thinking it’s detached HEAD even when it’s not. Make sure you use the Source Control menu to change branches.

That’s a lot of problems. The biggest advantage it has is that it’s not an external third-party solution; it’s integrated right into the Apple ecosystem so you have something of a guarantee that it’ll continue working with Xcode updates. It has very few configuration options (a huge plus in my book), seeming to focus on convention-over-configuration. This means you’ve got to setup your project in a way that makes the Xcode Server happy. This is not always easy, but if you get it right, Xcode Server will be able to build your application on-demand, on a schedule and you’ll have something of a guarantee that your app is as simple to compile as:

- Clone repo.

- Open

.xcworkspace. - Press big play button.

Optimise Your Environment For Maximum Non-Suckery

One of your first aims here should be to absolutely reduce the amount of special configuration that is required to compile your project. Configuration includes things like:

- Custom build scripts

- Special (particularly user-defined and undocumented) compiler flags

- Unsupported or deprecated build options (like armv6)

- Makefiles

You’d be surprised how much you can do by staying within the confines of the standard Xcode project settings. There’s almost always a way to do what you’re trying to do with custom build scripts or Makefiles using just build configurations, targets and schemes.

Building Shouldn’t Change Anything In Source Control

The build process should only ever modify build products, not source

files! A particularly notorious example of this is modifying your Info.plist

file before building. Please don’t ever do this! Modifying the Info.plist

is pretty common for inserting build-related information such as the git

commit, build date and so on for debugging purposes. You could even do this

to switch out the bundle ID so you can have development, staging and production

versions of your app on a device at the same time. In this particular case,

the correct thing to do is to edit the Info.plist in the .app file after

it’s produced, but before codesigning happens. A very good example of this can

be found here. If you need to change your bundle identifier, typically

what I do is:

- Create a unique configuration for every bundle identifier. I usually

duplicate the release configuration and modify it suit the debugginess

of the particular build, for instance staging builds have

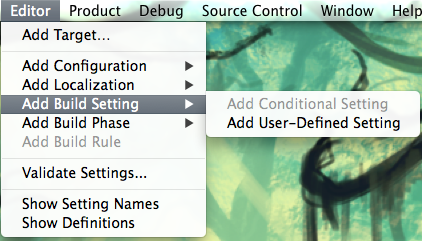

DEBUGdefined but release do not. - Create a User-Defined build setting to specify the bundle identifier. This

option can be pretty difficult to find so see below for a screenshot of the

menu option. You can name the setting something like

MYAPP_BUNDLE_IDENTIFIER. If you change from Combined to Levels, you’ll now be able to change the value per-configuration. This value will now be exposed in the script in Build Phases under Run Script as${MYAPP_BUNDLE_IDENTIFIER}.

Anything that gets modified as part of the build process should be considered

a build product, and all build products should be in your .gitignore file

(or similar, if you’re still using legacy version control systems). The ideal

scenario is this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

$ git clone <myrepo>

Cloning into '<myrepo>'...

...

$ cd <myrepo>

$ xcodebuild

=== BUILD TARGET MyAwesomeApp OF PROJECT MyApp WITH THE DEFAULT CONFIGURATION (Release) ===

...

$ git status

# On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

If you managed to get your terminal into this state, congratulations! You’re one step closer to having an un-fucked build environment!

Everything Needed For Build Belongs In Version Control

This is the point that will perhaps be the most controversial. Xcode Server

has a bug as of the released version of OS X Mavericks Server, where if

something modifies the .xcworkspace or .xcodeproj during the build process,

the build will immediately fail. This is a huge problem if you use something

like CocoaPods. The typical attempt at trying to get CocoaPods to work

with Xcode Server usually involves creating some pre-build script that invokes

pod install. Sounds great in theory, except that pod install modifies the

.xcworkspace, .xcodeproj and the related Pods.xcodeproj, causing Xcode

Server to chuck a tantrum of biblical proportions. In light of this, I

propose we commit the ultimate heresy: We should commit the Pods folder to

git.

Now – please, put those pitchforks away – I realise that this means throwing

a huge amount of data into your git repository, and it kinda flies in the face

of the spirit of CocoaPods as a dependency manager, but hear me out. The

problem with not having the Pods folder in version control is that you’re

relying on some external state (the CocoaPods spec repo and all your

dependencies’ repos) to properly build your app. If one of your dependencies

updates their .podspec to support a newer version of CocoaPods but breaks

compatibility with your build server’s version of CocoaPods, then your app will

fail to build; through no fault of your own. When you think about it, there’s

quite a lot of beauty in checking in your Pods folder to version control:

- It shifts CocoaPods to being a part of the development toolchain, rather than the build toolchain. The only machines in your organisation that need CocoaPods (and the associated Ruby hell) are your development machines; more specifically, just the developer(s) that you’ve delegated to manage dependencies.

- Any commit in your version control history can be reliably built simply by checking it out and building it. There’s no chance that a tag which built one day will no longer build another day because the dependencies changed on GitHub. There’s still the issue that Xcode updates will break past builds, but at least you and your organisation are in control of that.

The Pods folder these days is almost exclusively source files anyway, the

exception being Pods that provide graphics and the like. Git is pretty darn

good at dealing with large amounts of source files, it’s when you’ve got

large binaries that things get hairy. Some dependencies (I’m glaring right

at you TestFlight, Google Analytics, Crashlytics, etc) simply

provide you a binary blob as a dependency. Unfortunately, in this case, just

commit it to git and hope for the best. They’re not that massive, and as

long as you don’t update them too often it shouldn’t be much of an issue.

An added bonus is it means Xcode Server will work! It also greatly simplifies

getting newbies set up in your project. Getting a new hire up to speed on the

intricacies of CocoaPods has always been the biggest stumbling block for us in

getting someone set up. Being able to simply clone the repo, open the

.xcworkspace and press build has an implicit value that’s really hard to

quantify, but you’ll know it when you see it.

One More Thing…

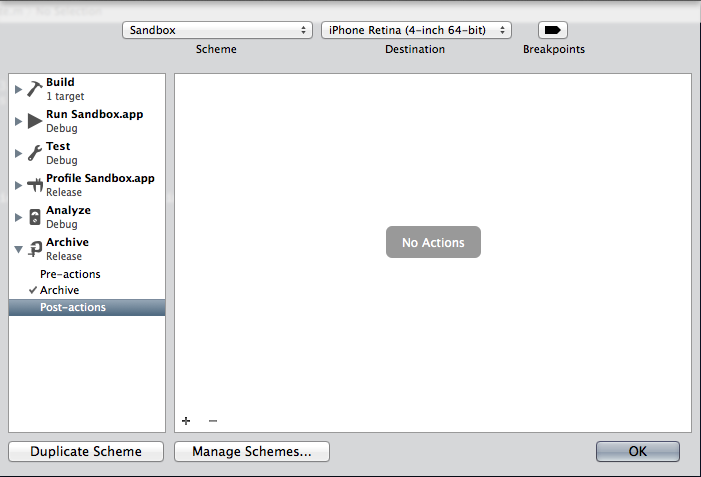

Lastly, if in Jenkins you had some post-build actions, it’s still possible to do this with Xcode Server as well. What you need is Archive Post-actions in the Scheme editor. A good strategy is to create a special Scheme for each of your Bots, and configure special Post-actions that’ll run after the archive has finished on the server.

Make sure you set the Provide build settings from options, so that all the same environment variables that get passed to Run Script scripts in your build get passed in, and a few extra ones. If you’re curious as to exactly what all the environment variables are, create a script like this:

1

env > /tmp/env

Then, archive your app and check out the contents of /tmp/env. Some interesting ones:

1

2

3

4

5

6

${PROJECT_DIR} # absolute path to folder containing the .xcodeproj

${ARCHIVE_PATH} # absolute path to .xcarchive

${WRAPPER_NAME} # name of the resulting .app file

${TARGET_NAME} # target that was compiled

${ARCHIVE_PRODUCTS_PATH} # absolute path to .xcarchive/Products

${ARCHIVE_PRODUCTS_PATH}/Applications/${WRAPPER_NAME} # absolute path to .app

This lets you do some really interesting things after an archive has finished,

such as automatically re-signing the app, creating an IPA with embedded

.mobileprovision, upload to TestFlight…

Keep in mind, on the build server this script will execute as the Server’s

_teamsserver user, which doesn’t have a home folder, let alone a desktop

environment. This means if you’re doing funky stuff, such as with SSH or the

keychain, you’ll need to be wary of the constraints. This can get really

complicated so I might dedicate an entire post to this topic in the future.